Executive Summary

In the face of deepening globalisation, the world has experienced a shift in global supply chains, with production processes dispersed across countries and regions. This distributed model has propelled countries like China, Thailand, and Vietnam to remarkable economic growth and heightened productivity. However, global headwinds and the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted these global supply chains, compelling nations and businesses alike to review their globalisation strategies.

As a critical player, China has not been immune to these impacts. Our British Business in China: Sentiment Survey 2022-23, highlighted that supply chain uncertainties are rooted in both global and local supply chains, and most notably impact goods businesses, with retail and consumer goods (79%), energy (78%), and advanced manufacturing and technology (75%) sectors all reporting being impacted. Perhaps as a reflection of these uncertainties, those in the business of providing goods more often indicated that China was a medium priority for their global investment plans in the coming year (31%).

Unsurprisingly, businesses are increasingly considering the structure of their supply chains with varying approaches to future investment strategies in their China manufacturing capabilities. While some consider offshoring some business functions out of China (19%) or onshoring some functions into China (6%), others contemplate exiting China entirely (7%). Similarly, potential relocation of manufacturing functions (8%) and sourcing components (6%) highlights the need for strategic planning in a slow process of supply chain reorientation. Whilst this has raised concerns over potential industrial hollowing and a potential decline in China’s global competitiveness, historical trends demonstrate that such shifts are inherent in economic progress, and countries can mutually benefit from the repositioning of industries.

The success of any supply chain restructuring lies in embracing market-driven principles which allow the market to function freely and effectively. That said, the process for reorienting supply chains is slow, and a roundtable discussion hosted by the British Chamber of Commerce in Guangdong indicated that China’s depth of supply chains and corresponding infrastructure, combined with its capacity and agility to adapt and change, meant that China continues to have a competitive market position in terms of global industrial supply chains. The ability for China to continue to thrive in the evolving global supply chain landscape will depend, in part, on the continued strengthening of China’s scientific and technological progress, enabling industrial upgrades. By doing so, China can continue to propel its economic growth and enhance its resilience.

Navigating the evolving global supply chain landscape demands a strategic and proactive approach. By capitalising on strengths, embracing innovation, and maintaining market-oriented policies, China and British businesses can navigate geopolitical shifts and supply chain complexities to achieve sustained growth and prosperity in the global market.

The Policy Insights article below is authored by Professor Li Haitao, Dean’s Distinguished Chair Professor of Finance and Associate Dean, Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB). It was originally published on June 7, 2023, on CKGSB Knowledge and is accessible here.

Introduction

Global supply chains are changing and China may fare better by approaching this shift with a more open and market-oriented approach

Deepening globalisation has been the main factor behind human societal development, particularly over the past century. Between 1990 and 2007, globalisation developed at its quickest rate, thanks to the upgrading of transportation infrastructure, advances in communication technology and the lowering of trade barriers. These changes, fueled by a desire for greater efficiency and cost reduction, have reshaped the supply chains of almost all industries around the world.

In this globalised supply chain model, production processes are distributed to different countries or regions, which tend to focus on specific production stages, rather than completing the entire production process alone. As a result, larger multinational companies are often shuttling components and semi-finished products around the globe, between smaller specialised suppliers.

The result of the global distribution approach is that countries that are active participants, such as China, Thailand and Vietnam, have all experienced a boost in productivity and income to various extents.

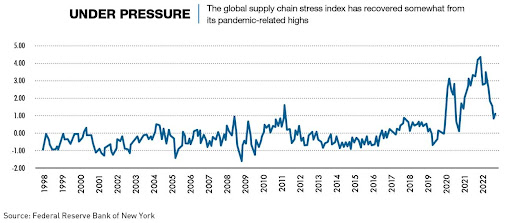

But the reversal of the globalisation trend in recent years is challenging these globally-diverse supply chains, the expansion of which began to slow after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. More recently, US-China trade tensions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict have increased pressures on supply chain layouts.

The pandemic has had an extremely negative impact on the global economy, across the supply side, demand side and distribution chains.

In the first half of 2022, for example, the number of container ships waiting at the port of Shanghai and the nearby port of Ningbo Zhoushan more than doubled after a virus outbreak in Shanghai and surrounding areas. Because of the resulting delays, the production flow of major companies, including Tesla and Honda, was greatly affected, and supply chains around the world were disrupted.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has had a massive impact on the global supply chain. The first is its effect on the supply of a large number of commodities. Both Russia and Ukraine are important sources of oil, gas, grain and many non-ferrous metals, and as long as the conflict continues, the regularity and quality of supply of all of these products will be affected.

The second major impact has been Russia’s increasing exclusion from global institutions and supply chains. Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the United States, the European Union and other Western countries have imposed sanctions on Russia, removed the country from various trade organisations and many multinational companies have withdrawn from the Russian market. Major Russian banks have been excluded from the SWIFT payment system, and their overseas assets have been confiscated or frozen.

These factors have dealt a blow to the status quo of the global multilateral trading system, with political decision-making being prioritised over existing trade rules. Due to the wide-ranging sanctions placed on the country, the Russian economy is now in the process of decoupling from the Western economy, which has hurt the globalisation of supply chains.

According to the Global Supply Chain Stress Index, produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, there has been an obvious increase in pressure on global supply chains since early 2020, and these pressures show no sign of abating.

Based on the pressure on global supply chains and the changes in the international political and economic environment, countries and many enterprises around the world have started to rethink their globalisation strategies, and the restructuring of global supply chains has become a new trend.

Impact on China

Supply chain restructuring is bound to have a huge impact on the economic development of countries around the world, and as the so-called factory of the world, China will certainly see major changes.

The country has already started to see an outward shift of manufacturing capacity in several industries. Looking at electronic equipment manufacturing, Samsung closed all of its smartphone factories in China in 2019, making Vietnam the company’s largest production base outside of South Korea. Over 50% of Samsung’s cell phone exports and one-third of its electronics shipments are now produced in Vietnam.

In April 2022, ON Semiconductor, a leading global chipmaker, announced that it would relocate its Shanghai distribution centre, one of its four distribution centres in Asia, to Singapore and would close its global distribution centre in China.

China’s share of furniture imports by monetary value into the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea has dropped from 52.8% to 43.5% between 2018 and 2020, and the proportion of telecom devices has dropped from 62.6% to 57.4%. Vietnam replaced China as the largest furniture supplier to the US in 2020, with Vietnam’s wood products and furniture exports amounting to $14.5 billion, in 2021, up 17.2% year-on-year.

A similar offshoring trend is also apparent in the textile industry. Since 2014, Tianhong Textile, one of China’s largest cotton textile manufacturers, has been developing the Haihe Industrial Park in Vietnam, with plans to create a full supply chain base, going from raw material production to processing and sales. Chinese coloured yarn spinning giant Blum Oriental has also already relocated 60% of its total capacity in Vietnam and plans to expand its output there by another third.

This outward flow of manufacturing has resulted in concerns that there may be a hollowing out of Chinese industries and a general reduction in the country’s global competitiveness. But it is important to note that supply chain shifts are not a new phenomenon, and many even larger-scaled industry shifts have occurred across modern economies.

For example, after the middle of the 19th century, along with the industrialisation process of the United States, European industries moved across the Atlantic on a large scale. Secondly, after World War II, along with the post-war reconstruction process, parts of US industries moved to Europe, Japan and other places. Thirdly, in the 1970s, some Japanese industries such as home appliances and chemicals were transferred to South Korea, Taiwan, Southeast Asia and other regions.

Having said that, with the development of the Chinese economy and the improvement of living standards across the country, some of China’s original advantages, such as cheap and abundant labour supply, have gradually diminished. And under such circumstances, some industries are bound to choose new manufacturing locations that can offer greater comparative advantages.

This type of industrial transfer is consistent with economic trends, and both parties can benefit from the shift. Taking ASEAN, the largest destination for China’s industrial out-migration, as an example, in 2020, ASEAN replaced the EU as China’s largest trading partner. In 2021, China’s exports to ASEAN amounted to $483.69 billion, up 26.1% year-on-year, and imports from ASEAN amounted to $394.51 billion, up 30.8% year-on-year, showing a clear benefit on both sides of the relationship.

Letting the market work

The inevitability of the global supply chain shift is set out by the laws of the market. However, it is vital that the market is allowed to function properly while this transformation takes place.

In recent years, the view of many is that the US has launched industrial policies aimed at safeguarding its interests, which could have a detrimental effect on the market’s ability to properly regulate itself.

An example is that the US used the US-China trade deficit as a justification to substantially raise tariffs on imports from China. The average tariff rate on Chinese products exported to the United States rose from 3.8% in June 2018 to 19.3% in mid-2022, and these tariffs cover approximately 66% of Chinese exports to the US. Non-market-based tariff increases have hurt normal trade between the US and China and have hurt the world economy.

In May 2022, the US also announced the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) program, which consists of 13 countries, including the US, Japan and India, and accounts for about 40% of the global economy, but does not include China. US Trade Representative David Deitch has publicly stated that the IPEF is a “China-independent arrangement.”

There is also the example of the Chip and Science Act introduced in the United States. The bill explicitly requires that 40% of the mineral materials used in new energy batteries be mined and processed by countries with which the US has free trade agreements, and this percentage will rise to 50% by 2024, 80% by 2027, and 100% of battery components must be manufactured in North America by 2029.

Among the world’s major economies, China is the only country that is competitive in the new energy industry but does not have a free trade agreement with the United States.

Restructuring response

China’s response to the global supply chain restructuring will define its future role in global development, and there are several areas where the country must focus its efforts. First, China’s future economic development will increasingly correlate with its scientific and technological progress, which will facilitate industrial upgrading, going a long way to mitigating the effects of the global supply chain shift.

China’s investment in scientific research has been increasing in recent years, and the contribution of scientific and technological progress to economic growth has, in turn, been rising.

Secondly, while strengthening its research investment, it can’t simply close its doors. It should be noted that in many fields, the developed Western countries are still in a leading position compared to China, and learning from other countries, including the US and Europe, is still an important way for China’s economy to improve.

China’s photovoltaic (PV) industry is a good example of successful industrial upgrading through external learning. Before the 1990s, China’s PV technology and industrialisation levels were very weak, and almost all PV products were imported. At present, China’s PV industry is already a global leader and its products not only meet China’s domestic demand, but are also exported to over 200 countries and regions.

The analysis of the industrial chain shift shows that passive resistance or resignation to the fate of the global industrial chain restructuring is not the way to deal with it, but active adaptation to the changing environment is the right response.

For some domestic industries that have lost their competitive advantages, it is wise to take the initiative to move to more competitive countries or regions. A more important direction of development is to increase their technology and innovation capabilities.

But it is worth remembering that, with the world’s largest single market and a rich engineer’s dividend, China is still very competitive in this new configuration of global industrial supply chains.

This Policy Insights article was authored by Professor Li Haitao, Dean’s Distinguished Chair Professor of Finance and Associate Dean, Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB). It was originally published on June 7, 2023, on CKGSB Knowledge and is accessible here.

Established in Beijing in November 2002, CKGSB is China’s first privately-funded and research-driven business school. The school aims to cultivate transformative business leaders with a global vision, sense of social responsibility, innovative mindset, and ability to lead with empathy and compassion. Today, CKGSB stands apart for its full-time, world-class faculty, research excellence, China insights and unparalleled alumni network. More than half of its 40 strong faculty members previously held tenure or senior professorships at top business schools, such as MIT, Wharton, and Yale. CKGSB is also the preferred choice for management education among China’s established business leaders and a new generation of disruptors. More than half of its 20,000 alumni are at the CEO or Chairman level and, collectively, they lead one fifth of China’s 100 most valuable brands.